The Body Politic Grows Soft and Fat

By Wesley Pruden

WashingtonTimes.com

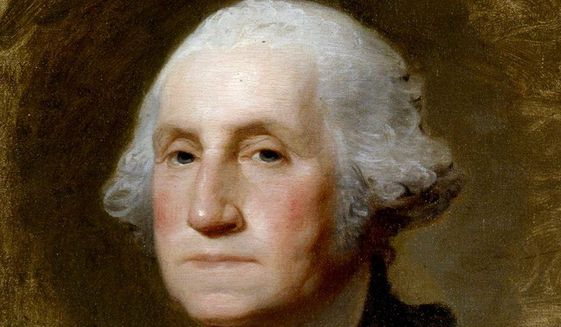

George Washington From a

portrait by Gilbert Stuart

The Founding Fathers tried to warn us about runaway partisan outrage, but they didn’t listen to themselves. We’ve been paying for it ever since. Now there’s not much we can do about it.

George Washington understood what was coming with the birth of political parties, which he, like other Founding Fathers, called “factions.” The word was pronounced with a sneer. The wrangling of political parties, the aggregations of selfish and greedy “self-interests,” Washington observed, always “agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one party against another.”

Thomas Jefferson, who always got quickly and colorfully to the point, vowed that “if I could not go to heaven but with a party, I would not go there at all.”

Wherever they are, if they’re still reading the morning paper, they can see writ large what they were talking about: agitations, ill-founded jealousies and false alarms that would make the nation almost ungovernable. One party is a congeries of feminists, gays and blacks who see every issue through a single lens, focused only on what is important to their faction. Another party is a congeries of voters who talk mostly of what Mike Huckabee calls “God, guns, grits and gravy.”

The trouble begins when the factions take over a political party and it becomes a congeries of shrill and uncompromising factions, and the voter confuses loyalty to faction and party interests with loyalty to the country’s interests. Elections become occasions to see which factions have taken over which parties.

Hillary Clinton ran in 2008 with disdain for the notion that her election would be good because she would be the first woman president. This time that notion is the mantra for her campaign. She says she wants to be, not necessarily the best president, but the first woman president.

Such resolve appeals to certain women of the feminist persuasion, who are terrified of being identified as a self-loathing, bigoted woman willing to think for herself, and eager to betray her own kind. Such feminists rarely have an inquiring mind that wants to know. They got the memo that the American mind is now closed.

Choosing a president only because a candidate looks like you and sounds like you is risky business. Many white Southerners who should have known better voted for Jimmy Carter because they were seduced by his voice, the first in the White House in a long time to speak without an accent. Mr. Carter, alas, governed as if he had washed from his heart all traces of the Southern verities — toughness, loyalty and a taste for fighting against pernicious influences until the last dog dies — and left office after only one term with the reputation of a wimp who sups only on mush and blue john.

Millions of black voters were similarly seduced by the prospect of seeing a president who looked like them, and they (and the rest of us) see how that worked out. Black and white will be paying for that flight of foolish fancy for a long time to come.

We might have had this unfortunate result in any event. Human nature, with all its jealousies, jaundices, grudges, mistrusts and heartburns, drives us inexorably to a faction, the common good be damned. It’s only important to get what we want. Human nature, despite the occasional evidence to the contrary, afflicts everyone, across every conspiracy, faction and party.

The original American ideology depended on the subordination of narrow and selfish interests to the greater good. Politics was meant to be collaborative, not competitive. The language of the Constitution reflects this desire by the Founding Fathers, and required clever lawyers to find effective ways to subvert it.

Now the damage is done. Political parties thrive even when the nation doesn’t. The Founders and their philosophy were descended from educated English thinkers and doers, small-R republicans all), who could not imagine how plain language could be so easily corrupted and twisted by lawyers — and judges — of dubious honor. They imagined that the political process was about first identifying the common good, and then trying to find a way to promote that good.

If the body politic broke up into small tumors and lesions, the search for the common good would fail. Jefferson thought that a republic, such as the one the Founders bequeathed, would survive, and prevail, until the masses learned to plunder the public treasury. The electorate would then evolve (the currently fashionable word for “mutate”) into factions of selfish winners and bitter losers to fight over what would make up the common good. To see how that’s working out, look around you.

• Wesley Pruden is editor emeritus of The Washington Times.