JFK Opposed Trump-Style Impeachments

By I&I Editorial

IssuesInsights.com

An unwelcome ghost haunts the U.S. Senate this week as it takes up the dubious charges against President Donald Trump: the disembodied spirit of a slain president who six decades ago spoke from a desk near the back of the Senate chamber.

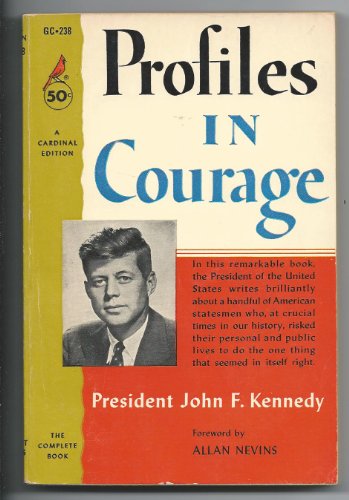

Massachusetts Sen. John F. Kennedy in 1957 won the Pulitzer Prize for biography for his portrait of eight of his predecessors in the World’s Greatest Deliberative Body, “Profiles In Courage” (even though speechwriter Ted Sorenson ghostwrote almost all of it), and the notoriety helped propel him to the highest office in the land several years later.

The fifth courageous senator JFK profiled in the bestselling volume was Edmund Gibson Ross of Kansas, unexpectedly responsible for the deciding vote that acquitted President Andrew Johnson in his Senate impeachment trial in 1868. Kennedy proclaimed Ross a hero who saved the presidency from congressional overreach.

There’s no denying, of course, that impeachment of a president is political. The Framers designed it that way. The misdeeds for which an elected official would be impeached and removed “are of a nature which may with peculiar propriety be denominated political,” Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist 65, “as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself. The prosecution of them, for this reason, will seldom fail to agitate the passions of the whole community, and to divide it into parties more or less friendly or inimical to the accused.”

The president of the United States “is impeachable for any crime or misdemeanor, before the Senate, at all times,” James Madison told Congress in June 1789, and “he is impeachable before the community at large every four years, and liable to be displaced if his conduct shall have given umbrage during the time he has been in office.”

But the first time the impeachment of a president happened, a post-Civil War Congress, filled with radical Republicans intent on grinding down all remnants of the antebellum South, and furiously impatient with Johnson’s disinclination to go to such extremes against his countrymen on the losing side, abused the awesome powers of removal the Constitution gave it with its 11 articles against the 17th president.

According to the future President Kennedy, Ross “may well have preserved for ourselves and posterity constitutional government in the United States” by performing “what one historian has called ‘the most heroic act in American history, incomparably more difficult than any deed of valor upon the field of battle.'”

Haunting Parallels In Congressional Abuse of Power

JFK’s 60-plus-year-old analysis at times seems to be uncannily referring not to a Republican Party ideological extreme in the mid-19th century, but to the crazed left of the Democratic Party of today.

Of the Senate taking up the articles against Johnson, Kennedy wrote that “as the trial progressed, it became increasingly apparent that the impatient Republicans did not intend to give the president a fair trial on the formal issues upon which the impeachment was drawn, but intended instead to depose him from the White House on any grounds, real or imagined, for refusing to accept their policies.”

Years of certainty on the part of Democrats that Robert Mueller’s investigation would produce a rationale to impeach Trump reflects perfectly their intent “to depose him from the White House on any grounds, real or imagined” – and Trump’s dogged conservatism points to their motive being Trump’s “refusing to accept their policies.”

Kennedy went on: “Telling evidence in the president’s favor was arbitrarily excluded”; he could have been talking about Democrats opposing hearing from Hunter and Joe Biden in the Senate trial. “Prejudgment on the part of most senators was brazenly announced”; the vast majority of Democratic senators today clearly have every intention of voting to convict Trump, no matter what happens in the trial. (Granted, there’s little doubt too that the vast majority of Senate Republicans already know they’ll be voting to acquit the president. But then they haven’t been shown much of anything that resembles a high crime or misdemeanor.)

The most striking parallel to the Trump impeachment, however, is that Ross and the other GOP senators who voted against removing Democrat Johnson fully appreciated how disliked Johnson was; they knew, however, that that could not serve as license for such extraordinary means of removing him from office, a power more properly reserved to the voters.

Kennedy quoted Sen. William Pitt Fessenden of Maine, who said, “The country has so bad an opinion of the president, which he fully deserves, that it expects his condemnation.” But Fessenden maintained that “The question to be decided is not whether Andrew Johnson is a proper person to fill the presidential office, nor whether it is fit that he should remain in it.” He warned that “Once set, the example of impeaching a president for what, when the excitement of the House shall have subsided, will be regarded as insufficient cause, no future president will be safe who happens to differ with a majority of the House and two-thirds of the Senate on any measure deemed by them important.”

As JFK related, Fessenden asked, “What then becomes of the checks and balances of the Constitution so carefully devised and so vital to its perpetuity? They are all gone.”

Another Republican, Sen. Joseph Smith Fowler of Tennessee, “at first thought the president impeachable,” according to JFK. “But the former Nashville professor was horrified by the mad passion of the House in rushing through the impeachment resolution by evidence against Johnson ‘based on falsehood’” – the comparison to Trump again being remarkable, with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi rushing the impeachment inquiry over the course of only 48 days late last year so as to get a House floor vote to impeach done before Christmas.

Ultimately, Johnson was thoroughly vindicated. His supposed offense was violation of the Tenure of Office Act, passed by Congress in 1867 over Johnson’s veto for the purpose of preventing Johnson’s removal of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, who was intent on the harshest Reconstruction policies against the former Confederate states. Congress would repeal the law in its entirety in the 1880s; the Supreme Court would later determine the law to have been unconstitutional; and after he completed the tenure of his presidency, Johnson himself was triumphantly elected senator by the state lawmakers of his native Tennessee – still to this day the only former president to sit as a U.S. senator.

The Democrats claim Trump tried to “pressure a foreign government to interfere in a United States election for his personal political gain, and then attempted to cover up his scheme by obstructing Congress’ investigation into his misconduct.” It’s one thing when Republican senators take issue with such a long stretch of the truth. It’s another thing altogether when the voice of one of the Democratic Party’s most esteemed icons echoes GOP objections from his Arlington grave.