Divided We Stand

By Daniel Greenfield

SultanKnish.Blogspot.com

Time brings distance to all events. No pain is as fresh twenty years later as on the day it happened. The shock of the impossible becomes the new normal and then it becomes more background noise.

"A single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is

a statistic," Joseph Stalin said. The statisticians

in Doha, Tehran and Riyadh know it quite well when

they count up their numbers. Compound death is more

than a statistic; it is incomprehensible.

The banal media coverage of September 11 grapples

with a story too big to tell that can only be broken

down into human fragments of personal stories.

This is true for most of the dark footprints of

history. There is no story of the Holocaust, there

are only countless personal stories of survivors and

the procedural story of the Nazi killing machine.

These perspectives never come together into a single

story only human fragments and procedural details,

the departments and mechanisms, how many milligrams

of Zyklon B it takes per kilogram to kill a person

and how many people can be loaded on a train in how

much time.

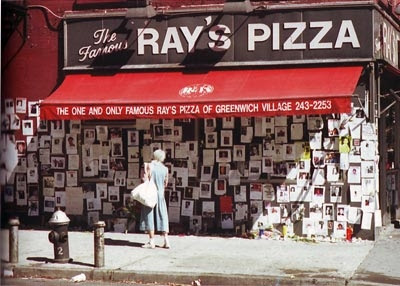

The coverage of 9/11 breaks down into these same

mini-stories, survivors describing how they escaped,

the families of the dead relating how they reacted

to the news, the stories of firefighters and

officers, and the procedural questions, how long it

takes a falling body to achieve terminal velocity

and what happens to the human body when it breathes

in enough ash and soot. On the other side are the

killers who plotted and planned, checked flight

schedules, got their boxcutters and their korans and

killed thousands for Allah.

The story of the attacks cannot be told because

there is no boundary to it. Where do we begin, with

a handful of upper class Muslims in Hamburg? With a

scion of the Bin Laden clan becoming a Ghazi or with

Hassan Al-Banna finding inspiration in Third Reich

propaganda to modernize Islamism? With the Gates of

Vienna, the Shores of Tripoli or Mohammed in Mecca?

All but the last are incomplete, and even the last

leaves too much out.

When a murder happens we trace back the motives of

the killer. Was he abused as a child, did the

authorities fail to act in time, what made a once

sweet boy turn into a killer? To do the same for

September 11 is to travel back over a thousand years

and still come away with few answers except that

sometimes human evil can be congealed into an

ideology and passed along from generation to

generation like a virus of hatred and cruelty.

"Where were you when the planes hit," attempts to

orient us in time. But the question is only an

attempt to make the impossible seem real. The

businessman covered in ash and stumbling over the

Brooklyn Bridge and the Seattle housewife waking up

to see news coverage of it on television are more

human fragments of a thing that is more than human.

War.

War fragments perspectives, and though we have grown

used to formal stories of war which began with a

legal declaration of war and end with a surrender,

these things have as little to do with war as a

coroner's statement has to do with death. The laws

of war, the treaties and the formalities are ways

that human civilization attempts to make the wild

force of human nature into a manageable thing.

Europeans and their colonial descendants may pen

laws of war, but only they are constrained by them.

In the real world outside the dinner parties of

Washington D.C. and Brussels, there are no laws in

war. Islamic law which has regulations for which

foot to use when entering a bathroom (the left foot)

and which side to sleep on (the right) has very few

laws of war that cannot be nullified by necessity or

even whim. On the battlefield, Islamic jurisprudence

is boiled down to, Do what thou wilt in the cause of

Allah, that is the whole of the law.

The West has tried to make war into a moral force by

governing its means, without regard to its ends. But

in the Muslim world, war is moral so long as its

ends are Islamic-- the means are a technicality that

Islamic scholars may squabble over the way they do

over every petty matter, but in practice it's

anything goes so long as it serves the Ummah. And

even those technical debates over civilians in war

and terrorism are governed by the ultimate welfare

of the Ummah.

What happens when people who believe that the ends

justify the means fight against people who believe

that the ends never justify the means? In

Afghanistan and Iraq the people who believed that

the ends justify the means have gained their ends--

while we have lost both the ends and the means, not

going far enough for the hawks and going too far for

the doves.

This is the broken way of war that we practiced

in Vietnam and Korea, constrained by invisible

boundaries of our own making that did not prevent us

from bombing cities, but did keep us from wiping out

entire villages. To our enemies, these morals of

ours seem every bit as senseless as their foot

washing regulations seem to us. Why do the people

who bombed Dresden beat their breasts over Mai Lai,

and why was Shock and Awe acceptable, but not Abu

Ghraib?

The answers invariably come down not to some

externally consistent philosophy or divine law, but

our need to feel good about ourselves by setting up

a code that makes us seem moral in our own eyes.

That makes us feel good about war. And the first law

of that code is that killing en masse without really

meaning to is more moral than pointing a gun at a

man and pulling the trigger. This is the plausible

deniability morality of the firing squad which uses

enough dummy cartridges so that no one can be sure

who fired the shot. No wonder drone attacks are a

favorite of an anti-war administration putting as

much automation and distance as possible between the

soldier and his target.

Laws tell much about a people. Our need to legislate

the use of force, and their need to legislate

everything but the use of force. We have learned to

be afraid of our lurking potential for evil.

It is a fear absent in Islam where a man who serves

Allah cannot be a devil no matter what he does, but

we know all too well that the devil can come wrapped

in a saintly cause. We know it so well that we

sometimes forget that while devils do occasionally

come wearing halos, mostly they come wearing horns.

To our great pain and woe, we have forgotten that we

are not our own enemies.

A hundred years ago the attacks of September 11

would have marked the beginning of a war, but in

this century they only marked a day of pain and

sorrow, and years of a war that was never truly a

war. It is this conflicted un-war that the

anniversary marks. A war that never ends, because it

never began.

War is a framework for violence, which the Muslim

world hardly needs. While we search for an enemy to

declare war on, all they need is a Fatwa with a

clerical argument dubbing us the enemy, our nation,

our soldiers, our civilians and our children. All of

us.

We have no comfortable war framework except nation

building which pretends that war is really the Peace

Corps with bombs, habitat for humanity with the

homes blown up before they can be rebuilt.

Are we fighting because they attacked us or because

girls in Afghanistan can't go to school or for some

figment of regional stability in a country where

stability isn't even a word. That lack of clarity is

fragmentation. And fragmentation makes all stories

seem senseless.

The pain and shock of the attacks gave us a measure

of clarity. We were hit hard enough that we felt

once again that justice was on our side and we no

longer had to feel guilty for standing up for

ourselves. In a society whose highest morality has

become that of the victim, we were suddenly victims

and entitled to defend ourselves.

The need to question ourselves temporarily went away

and it felt good. For a brief shining moment the

country became aware of external enemies and was

united. We stopped being fragments warring with each

other and we became Americans.

Had that clarity been sustained, the country today

would be a dramatically different place. But it

diminished and fell apart, and our identity went

with it.We were once again our own enemies and the

real enemy went unrecognized. Now the anniversary of

the attacks has become like the memory of an old war

that was fought once, but no longer really matters.

The nation is at war, but it doesn't know that it's

at war. And those who know that we are at war, often

can't even state who the enemy is.

Without that clarity and unity, all we have are

fragments, individual stories without the means to

wrap them together. Stalin was right, a million

deaths is a statistic unless you find a way to bring

together what it means to an entire people. For the

Holocaust, it was "Never Again." For 9/11 it was a

more ambiguous, "United We Stand", but what do we

stand for and what do we stand against?

The anniversaries have long since been reduced to a

national therapy session, with pain released and

healed in the media's own talking cure. But it isn't

the pain that matters, it's what we do with it that

counts. We have not yet lost the war-- but we are

losing it, and unless we decide as a nation what we

stand for and what we stand again, then we will

lose. It will take time, like our banks we are too

big to fail, but given enough appeasement, enough

immigration and enough terrorism-- it will come.

Over a decade of war has passed, and before that

a thousand years of war with lulls and pauses, but

the din of the scimitar being sharpened for war

never truly stopped. Each year that passes is a

chance to learn the lessons of the years that have

gone by and to remedy their mistakes. The best way

to pay tribute to the dead is to unlearn our

mistakes so that what happened to them will not

happen again. Everything else is the fragmentation

of self-indulgence, the therapy of tears, the

sensitivity of grief, that will ease our pain, but

not our fate.

Every man and woman must defeat their own doubts

before they can defeat the enemy. Only then they can

they battle the false reasonableness of the

consensus that denies war and the enemy, with a

consensus that briefly formed after the attacks and

that forms even more briefly after every attack, to

see ourselves in relation to the outside enemy. To

unite against that enemy and to rebuild our identity

around a common conflict with those who want to

subjugate and destroy us. It may be ten more years

before we are ready to do that, but as long as it

takes-- that unity is our only hope.

The raw reaction in the aftermath of an event is the

true one and the more distance we put between

ourselves and that reaction also increases our

distance from the truth.

The years of war have added layers of distancing

between that first raw reaction when we saw the

towers fall. And it is important this day to return

not only to the emotion of that moment, but to the

clarity that is our greatest weapon. Only that

clarity will end this war.