Trouble, trouble at the Olympics

By Wes Pruden

PrudenPolitics.com

Mitt Romney, the businessman with an eye for what's

going wrong, can't resist the temptation to critique

what he sees. A cliche-monger would call him a

"problem-solver." Others would call him a pain in

the neck.

The presumptive Republican presidential nominee

arrived in London this week, took a quick look

around and observed the obvious, that neither our

English cousins nor the London Olympics appear to be

quite ready for prime time.

The man credited with saving the Salt Lake City

winter Olympics called the well-known problems with

security, traffic and a threatened strike by

immigration officers "a bit disconcerting." The very

word "disconcerting" is prim enough to suit the

diplomats who know which finger to crook over a cup

of tea, but not David Cameron, the prime minister

who scolded Mr. Romney for his plain language. Many

of the thousands of reporters in town naturally

called Mr. Romney's remarks a "gaffe," and suited up

in their goggles and flying suits for duty with the

dreaded Gaffe Patrol.

A

true gaffe is when a politician unexpectedly tells

it like it really is, so this may be an authentic

gaffe. The run-up to the London Olympics has been a

cluster of migraines for nearly everyone. They're

enough to make an Olympian forget where he put his

shot.

The prime minister, in his return fire, cited all

the good things his government has done to make the

London Olympics succeed, such as firing up enough

enthusiasm to recruit 8,000 "ambassadors" to be nice

to visitors, and sending the Olympic flame on a

70-day journey through the isles on its way to the

stadium for Friday's opening ceremony.

Even Mr. Romney mellowed his critique of Britons as

the Olympic torch, which originated at the site of

the original Olympics in Athens, approached the

stadium. "Do they come together and celebrate the

Olympic moment?" he asked. "That's something which

we only find out when the games actually begin." He

made nice as well with 10 Downing Street, while

slipping the needle to Barack Obama, telling a

fund-raiser rally for Americans in London that he is

"looking forward to the bust of Winston Churchill

being in the Oval Office again."

The bronze, by Sir Jacob Epstein, was lent to the

White House in 200l at the request of President

George W. Bush, an admirer of all things British,

and sent back to London at the request of Mr. Obama,

who is not much of an admirer of many things

British.

Controversy is nothing new to the Olympics, which

has from its origins, renewed with the founding of

the modern Olympics in 1896, nourished the conceit

that the games are a force for peace, justice and

other nifty things. "The day [the games are]

introduced the cause of peace will have received a

new and strong ally," said Baron Pierre de

Coubertin, the French organizer on the day the

modern games opened.

Not much peace has happened since, though the

Olympian bureaucracy still smears such treacle on

the games. "Through the Olympic spirit we can

instill brotherhood, respect, fair play, gender

equality and even combat doping," Jacques Rogge, the

current president of the International Olympic

Committee, said during the planning of the London

games. Not a lot of all that so far, either.

"Far from finding 'a new and strong ally' in the

games," writes the historian Andrew Roberts in the

Wall Street Journal, "the cause of world peace has

been betrayed by the International Olympic Committee

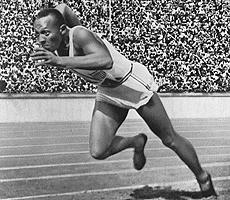

time and again." He cites the example of the Berlin

Olympics in 1936, awarded two years before Hitler

came to power but which der Fuehrer tried to make a

showcase for his racist theories. He was thwarted by

Jesse Owens, who gave the name "a goin' Jesse" new

meaning by winning four gold medals while Hitler

watched sullenly from the grandstand.

Though those games were awarded before Hitler came

to power in 1933, Mr. Roberts observes that 114

anti-semitic laws were put on the books by 1936, and

the International Olympic Committee resisted

withdrawing the games from Berlin. Avery Brundage,

an American who chaired the committee, argued that

since only 12 Jews had ever participated in the

Olympics nobody could blame the Nazis if no Jews

showed up for the '36 games.

This year the committee refused to make any

recognition of the 1972 Olympics, where Palestinian

guerrillas killed 11 Israeli athletes in Munich.

President Obama joined the international demand for

some sort of remembrance in London. The committee,

in the name of world peace, said no.

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Some world, some peace.

Wesley Pruden is editor emeritus of The Washington

Times.