By Daniel Greenfield

SultanKnish.Blogspot.com

Obama's predilection for turning his speeches into 'I' flavored confections is his unconscious and unselfconscious communion at that holiest of postmodern institutions, the cult of the self. It is a religion without faith, stripping away the deity and theology, leaving behind only the crisis of self-esteem. The great existential question of the cult of self is how to be happy. The resolution is invariably self-love.

Obama like few others is a man deeply in love with himself. His books are more than just a testament of self-love, they are the story of how he came to love himself. Like so many modern memoirs, it is a self-help tome dressed up in literary clothes. A note of encouragement to all of his followers who still haven't found the inner peace that comes from the self-absorbed mastication of biography, childhood memories and identity politics. The journey ends like every love story does, with the narrator embracing the object of his affection. The object of his affection being himself.

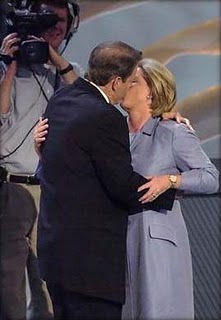

Al Gore's painful stage kiss with Tipper and suggestion that the frigid couple inspired Love Story were pathetic attempts to break his stiff reputation by validating himself as a man of deep feelings. The kiss, which resembled a woman being attacked by a drunken bear on the stage of the Democratic National Convention, did not successfully reinvent Gore as a passionate man. But his environmental activism, outsourced to ghostwriters and producers, eventually did the trick. And Al Gore finally attained the supreme ethical value of boomer liberalism, to be seen as a man who cares about things.

That need to be seen as a man who cares is a neurotic expression of the affective flattening, to hide the lack of real emotional response underneath. Gore betrayed his apathy, his depressive tendencies and self-doubt, with his stiffness. After decades of searching, the senator's son, like so many of his class, had still not transcended the burden of his privilege, instead he went on mummifying himself in the inauthenticity of politics. Doomed to play second fiddle to a con artist who had no such doubts because his own self-love gave him absolute confidence. A man he despised and was bound to by the fates of political charisma.

It was this self-love that made Obama seem like the third coming of JFK and Bill Clinton. While Carter and Gore had played the seekers, smelting their self-doubt into self-righteousness, these were the golden boys who never doubted to begin with. It was the quality shared by both John Edwards and Barack Hussein Obama, the two progressive favorites in the race. Two men whose optimism seemed to make everything possible. But the optimism of Edwards and Obama was not based on a calculated assessment of risk and reward. Instead it was based on their own faith in themselves. "Yes We Can" was not the slogan of intelligent determination, but of a blind faith in a personal awesomeness that overcomes all obstacles.

Obama was the messiah of self-esteem, a confidence boost for a generation taught to aspire to that as their highest value. It was not his policies that won him followers, but his self-assurance, spiced with some identity politics to appeal to the racial fetishism and orientalism of so many liberals. While millions voted for him in the hope that he would make things better-- as far as he was concerned, they voted for him, for being himself. His constant world trips, television appearances and magazine pullouts was his narcissistic way of repaying the voters by giving them more of what he thought they had asked for, The Gift of O.

Gore and Carter's public crises of self-doubt limned the profile of a liberalism whose empathy was the expression of a frenetic search for happiness by the confused and resentful children of the privileged. The princes and princesses who bitterly hate their kings and queens for never making them feel good about themselves. Their mingled sense of guilt, frustration at the burdens of destiny and their own secret fear that they could never live up to their fathers, led them to the pious hypocrisies of their liberalism. Not for its policies, but for its sense of absolution. The absolution of privilege and success in the fount of empathy. If only they could pretend hard enough to care about other people, maybe they could finally feel good about themselves. And then they could finally be truly happy.

Utopianism is escapism. Formalize utopia though and it becomes a restrictive creed, an iron treehouse with a thousand rules and ten thousand guards. Utopian philosophies account for dissent either with a surfeit of rules or no rules at all. The gulag or anarchy. And when anarchy fails, it's back to the gulag. There is a dream at the heart of the gulag, but it is a dead dream. A dove starved to death in a guard tower. Idealism which began as an escape from brutality turned to brutality in its execution. A turning away from evil made all the more evil in its turning on those whom it swore to protect. That is the long sad story of the left. A Janus with two heads one light and one dark, its tender sensibility flipping into cruelty.

Escapism is an unhappiness with the self met with an escape from a jailer who is also the self. But self-hatred is also an expression of self-love or self-obsession. Liberals wrestle with America, as they wrestle with themselves, their violent hate and bitter love, tied not to national history, but biography. They think that they are at war with their country, when actually they are at war with themselves. The self-hating American has this common with the self-hating Englishman, the self-hating Jew. and the self-hating men and women of every civilized land. The aborted children of The Enlightenment insisting on the supremacy of their childish sense of moral order through a regime of countercultural conformity.

The most iconic presidents have not necessarily been the most successful, but those who were best able to merge their own biographies with those of the nation at a crucial juncture. Washington's quiet paternalism, Jackson's rough confidence, Lincoln's humble uncertainty, Roosevelt's boisterous determination, Kennedy's youthful optimism and Reagan's momentous situationalism, became shorthand for the Americas of their time. There are fewer liberals on the list, because far fewer liberal presidents have been enough at peace with themselves to accomplish this.

The school of nervous eggheads and pretend eggheads, Woodrow Wilson, Adlai Stevenson, George McGovern, Walter Mondale and Al Gore, gave way to the school of the egotist, FDR, JFK, Clinton and Obama. And each successive class of the school of the egotist was also less competent than the previous. FDR and JFK had practically inherited their positions based on their last names. Clinton and Obama had taken theirs through aggressive media campaigns and faux empathy. Their self-confidence masked their self-destructiveness. Behind the smile was something else.

When George H.W. Bush was confronted with a mangled question by a functionally illiterate woman who demanded to know how the national debt had "affected him personally", it was as if the presidential debate had suddenly been displaced by a rerun of Donahue. Bush struggled to answer her question rationally, only to be told that he must answer how it had affected him personally. Clinton disregarded the confused phrasing that stymied Bush. He understood that it was an "I Feel" sort of question. Which demanded an "I Feel" sort of answer. Clinton's "I Feel Your Pain" moment was the perfect metaphor for the replacement of problem solving leadership with emotional mirroring. A skill cultivated mainly by actors and con artists.

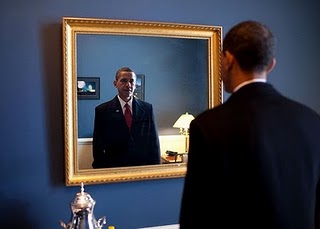

Clinton's empathy was refracted egotism. By convincing voters that he identified with them, he could make them identify with him. Obama hardly even bothered with the empathy. His entire public image was one long process of convincing the public to identify with him, filling them full of his biography over and over again, making them invested in his success and cultivating a false acquittance with them The King of I's made everything about him in a campaign that was all image. A vast hall of mirrors reflecting one lone figure standing on the stage. The camera lights flashed. The lights came on. A campaign that cost twice what the Apollo 11 moon landing had began. The Ego had landed.

It is the age of the King of I, who knows nothing and therefore has no need to learn it, who embodies hope for those escaping from themselves. The King of I lives out the dreams of others, but his own sleep is troubled. He has convinced his followers that he has nothing to run from anymore. But the truth is that he has never stopped running. His passionate public love affair with himself is a disguise. An older disguise than his family, but a disguise nonetheless.

He has made a fetish of authenticity, but it is a lie, and he knows too well that there is nothing authentic about him. When he looks into the mirror, he sees not himself, but a mirror in search of an image. And it is that mirror, the emptiness of the merely reflective, the boy who took on the quirks and traits of wherever he was, the eternal foreigner, that he is trying to escape. His followers believed in him, because they believed that he had found himself. That his own successful search for the self would enable him to find the true best self of the country. To lead them out of the bondage of their privileged selves, out of racial inequity and all forms of division and doubts, to the realization of the liberal utopia.

But for all his searching, the King of I had never found himself. Instead he discovered nothing but the mirror. Until he realized that he was the mirror. And there had never been anything else and never would be anything else but the mirror.