The Deficit Is Worse Than We Think

Normal interest rates would raise debt-service costs by $4.9 trillion over 10 years, dwarfing the savings from any currently contemplated budget deal.

By LAWRENCE B. LINDSEY

WSJ.com

Washington is struggling to make a deal that will

couple an increase in the debt ceiling with a

long-term reduction in spending. There is no reason

for the players to make their task seem even more

Herculean than it already is. But we should be

prepared for upward revisions in official deficit

projections in the years ahead—even if a deal is

struck. There are at least three major reasons for

concern.

First, a normalization of interest rates would

upend any budgetary deal if and when one should

occur. At present, the average cost of Treasury

borrowing is 2.5%. The average over the last two

decades was 5.7%. Should we ramp up to the higher

number, annual interest expenses would be roughly

$420 billion higher in 2014 and $700 billion higher

in 2020.

The 10-year rise in interest expense would be $4.9 trillion higher under "normalized" rates than under the current cost of borrowing. Compare that to the $2 trillion estimate of what the current talks about long-term deficit reduction may produce, and it becomes obvious that the gains from the current deficit-reduction efforts could be wiped out by normalization in the bond market.

To some extent this is a controllable risk. The

Federal Reserve could act aggressively by purchasing

even more bonds, or targeting rates further out on

the yield curve, to slow any rise in the cost of

Treasury borrowing. Of course, this carries its own

set of risks, not the least among them an adverse

reaction by our lenders. Suffice it to say, though,

that given all that is at stake, Fed interest-rate

policy will increasingly have to factor in the

effects of any rate hike on the fiscal position of

the Treasury.

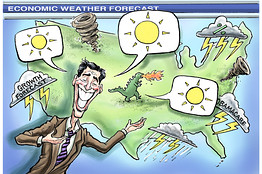

The second reason for concern is that official growth forecasts are much higher than what the academic consensus believes we should expect after a financial crisis. That consensus holds that economies tend to return to trend growth of about 2.5%, without ever recapturing what was lost in the downturn.

But the president's budget of February 2011

projects economic growth of 4% in 2012, 4.5% in

2013, and 4.2% in 2014. That budget also estimates

that the 10-year budget cost of missing the growth

estimate by just one point for one year is $750

billion. So, if we just grow at trend those three

years, we will miss the president's forecast by a

cumulative 5.2 percentage points and—using the

numbers provided in his budget—incur additional debt

of $4 trillion. That is the equivalent of all of the

10-year savings in Congressman Paul Ryan's budget,

passed by the House in April, or in the

Bowles-Simpson budget plan.

Third, it is increasingly clear that the long-run

cost estimates of ObamaCare were well short of the

mark because of the incentive that employers will

have under that plan to end private coverage and put

employees on the public system. Health and Human

Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius has already

issued 1,400 waivers from the act's regulations for

employers as large as McDonald's to stop them from

dumping their employees' coverage.

But a recent McKinsey survey, for example, found

that 30% of employers with plans will likely take

advantage of the system, with half of the more

knowledgeable ones planning to do so. If this survey

proves correct, the extra bill for taxpayers would

be roughly $74 billion in 2014 rising to $85 billion

in 2019, thanks to the subsidies provided to

individuals and families purchasing coverage in the

government's insurance exchanges.

Underestimating the long-term budget situation is

an old game in Washington. But never have the

numbers been this large.

There is no way to raise taxes enough to cover

these problems. The tax-the-rich proposals of the

Obama administration raise about $700 billion, less

than a fifth of the budgetary consequences of the

excess economic growth projected in their forecast.

The whole $700 billion collected over 10 years would

not even cover the difference in interest costs in

any one year at the end of the decade between

current rates and the average cost of Treasury

borrowing over the last 20 years.

Only serious long-term spending reduction in the

entitlement area can begin to address the nation's

deficit and debt problems. It should no longer be

credible for our elected officials to hide the need

for entitlement reforms behind rosy economic and

budgetary assumptions. And while we should all hope

for a deal that cuts spending and raises the debt

ceiling to avoid a possible default, bondholders

should be under no illusions.

Under current government policies and economic projections, they should be far more concerned about a return of their principal in 10 years than about any short-term delay in a coupon payment in August.

Mr. Lindsey, a former Federal Reserve governor and assistant to President George W. Bush for economic policy, is president and CEO of the Lindsey Group.