Mediscare: The Surprising Truth

Republicans are being portrayed as Medicare Grinches, but ObamaCare already has seniors' health care slated for draconian cuts.

By THOMAS R. SAVING

AND JOHN C. GOODMAN

WSJ.com

The Obama administration has repeatedly claimed

that the health-reform bill it passed last year

improved Medicare's finances. Although you'd never

know it from the current state of the Medicare

debate—with the Republicans being portrayed as the

Medicare Grinches—the claim is true only because

ObamaCare explicitly commits to cutting health-care

spending for the elderly and the disabled in future

years.

Yet almost no one familiar with the numbers thinks that the planned brute-force cuts in Medicare spending are politically feasible. Last August, the Office of the Medicare Actuary predicted that Medicare will be paying doctors less than what Medicaid pays by the end of this decade and, by then, one in seven hospitals will have to leave the Medicare system.

But suppose the law is implemented just as it's

written. In that case, according to the Medicare

Trustees, Medicare's long-term unfunded liability

fell by $53 trillion on the day ObamaCare was

signed.

But at what cost to the elderly? Consider people

reaching the age of 65 this year. Under the new law,

the average amount spent on these enrollees over the

remainder of their lives will fall by about $36,000

at today's prices. That sum of money is equivalent

to about three years of benefits. For 55-year-olds,

the spending decrease is about $62,000—or the

equivalent of six years of benefits. For

45-year-olds, the loss is more than $105,000, or

nine years of benefits.

In terms of the sheer dollars involved, the law's

reduction in future Medicare payments is the

equivalent of raising the eligibility age for

Medicare to age 68 for today's 65-year-olds, to age

71 for 55-year-olds and to age 74 for 45-year-olds.

But rather than keep the system as is and raise the

age of eligibility, the reform law instead tries to

achieve equivalent savings by paying less to the

providers of care.

What does this mean in terms of access to health care? No one knows for sure, but it almost certainly means that seniors will have difficulty finding doctors who will see them and hospitals who will admit them. Once admitted, they will enjoy fewer amenities such as private rooms and probably a lower quality of care as well.

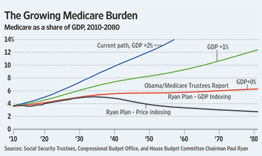

Are there better ways of solving the problem? The

graph nearby shows three proposals, including the

new law, and compares them to the current system.

For the past 40 years, real Medicare spending per

capita has been growing about two percentage points

faster than real gross domestic product (GDP) per

capita. Since real GDP per capita grows at just

about 2%, that means Medicare is growing at twice

the rate of our economy—and is clearly

unsustainable. If nothing is done, we'll see a

doubling of the Medicare tax burden in less than 20

years.

There are currently an array of proposals to slow

Medicare spending to a rate of GDP growth plus 1%.

These include a proposal by President Obama's debt

commission, chaired by Bill Clinton's former chief

of staff, Erskine Bowles, and former Sen. Alan

Simpson; one by former Clinton budget director Alice

Rivlin and Rep. Paul Ryan (R., Wis.); and another by

former Sen. Pete Domenici and Ms. Rivlin. Unlike the

Medicare Trustees, the Congressional Budget Office

(CBO) also scores ObamaCare at GDP plus 1%.

Of greater political interest is the House

Republican budget proposal, sponsored by Mr. Ryan.

This proposal largely matches the new law's Medicare

cuts for the next 10 years and then provides new

enrollees with a sum of money to apply to private

insurance (premium support). Even though the CBO

assumed premium support would increase with consumer

prices (price indexing), the resolution that House

Republicans actually voted for contains no specific

escalation formula. A natural alternative is letting

premium support payments grow at the annual rate of

increase in per-capita GDP (GDP indexing).

In light of the heated rhetoric of recent days,

it is worth noting that for everyone over the age of

55, there is no difference between the amount of

money the House Republicans voted to spend on

Medicare and the amount that the Democrats who

support the health-reform law voted to spend. Even

for younger people, the amounts are virtually

identical with GDP indexing.

The law's spending path depends on making

providers pay for all the future Medicare

shortfalls. But since no one can force health-care

providers to show up for work, short of a

health-care provider draft this reform ultimately

cannot succeed. The House Republican path, on the

other hand, would make a sum of money available to

each senior to choose among competing private

plans—much the way Medicare Advantage provides

insurance today for about one out of every four

Medicare beneficiaries.

That's a good starting point. But we believe that

a truly successful overhaul of Medicare will require

at least three additional elements.

First, there must be general system reform. You

cannot credibly hold senior health-care spending way

below everyone else's spending, nor can we make

taxpayers pay for all the future elderly's health

care. We must create a reform that reduces the rate

of growth of health-care costs for everyone—young

and old.

The best reform proposal for the non-elderly,

interestingly, is a health plan Mr. Ryan has

cosponsored with Sen. Tom Coburn (R., Okla.). It

would give all Americans the same tax relief for

health insurance and encourage market forces to

constrain costs.

Second, if federal spending is to be contained,

young people need to be able to save in tax-free

accounts during their working years in order to

replace the dollars they will not be getting from

Medicare.

Finally, providers need to be able to repackage and reprice their services under Medicare in ways that lower costs and improve quality. Anyone who saves Medicare a dollar should be able to keep 25 cents (or some other significant amount). Once that happens, private-sector innovations will spring up overnight.

Mr. Saving is director of the Private Enterprise Research Center at Texas A&M University and served two terms as a public trustee of the Social Security and Medicare Trust Funds. Mr. Goodman is president and CEO of the National Center for Policy Analysis.