Barrack Hussein McGovern

The specter of 1972 is haunting the Obama campaign.

By Mark Stricherz

WeeklyStandard.com

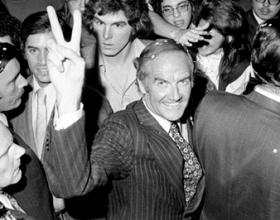

Forty years ago this summer, in July 1972, social liberals made their political debut at the Democratic National Convention. Gloria Steinem- and Gore Vidal-style activists were not shy about their goals. The women’s rights movement had secured two major victories that spring, Title IX funding and the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment in Congress, and cultural liberals hoped to secure two more at the convention in Miami Beach. “Ours is a pluralistic society, and I believe the Democratic party has an obligation no matter what the background of the individual candidates to include this issue as a fundamental right,” Sissy Farenthold, a candidate for governor of Texas, said in support of a plank favoring unrestricted access to contraception and abortion. “The various and diverse gay liberation movements realize that achieving liberation will require a new morality and an expanded understanding of human nature,” California delegate Jim Foster said in a plank urging the party to work to strike down anti-sodomy laws.

Both planks were defeated on the

floor. Even more important, many Democratic regulars

reached a conclusion that was as applicable then as

now: Cultural liberals forced the party’s

presidential nominee to run too far ahead of public

opinion on gay rights and feminism. Representative

James O’Hara of Michigan, the 46-year-old chairman

of a reform commission on party rules, said after

the election that McGovern’s association with the

-counterculture doomed his presidential bid: “The

American people made an association between McGovern

and gay lib, and welfare rights, and pot-smoking,

and black militants,

and women’s lib, and wise college kids, and

everything else they saw as threatening their value

system. I think it was all over right then and

there.”

How times have changed. Many national Democratic leaders have done more than tolerate cultural liberalism. Taking a page from the playbook of George W. Bush’s 2004 campaign, they are pinning President Obama’s reelection strategy on it. In an interview in May, senior campaign adviser David Plouffe described the strategy this way: “We’re gonna say, ‘Let’s be clear what [Mitt Romney] would do as president,’ ” he told New York magazine. “Potentially abortion will be criminalized. Women will be denied contraceptive services. He’s far right on immigration. He supports efforts to amend the Constitution to ban gay marriage.” Plouffe’s words have not fallen on deaf ears. Besides the administration’s mandate of free contraception and sterilization services in health insurance policies and Obama’s coming out in favor of marriage equality, the Obama campaign is running ads in swing states that accuse Romney of being an extremist on abortion.

Is running on social liberalism now the royal road to 270 electoral votes? Talk with political scientists and pollsters, and they say no, not really; this election will be decided on the state of the economy, or they say that Obama’s positions on gay marriage and abortion are a wash politically. “I would say [Obama’s gay-marriage stand] hurts him in empty-nest and service-worker communities,” says political analyst and author Dante Chinni, “but it helps him in suburban areas such as boom towns and college towns.”

Perhaps, but changes in demographics and attitudes may not have come as far as Obama campaign officials believe. According to an NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll in July, one in five voters said that the “decline of moral and religious values” is one of their biggest worries about America’s future, which outstripped their worries about the “increasing role of government” and “lack of safety/terrorist threats.” Millions of those voters are working-class and religious Democrats as well as independents.

Gay marriage is the issue most likely to hurt Obama. After his announcement on May 9 that he had changed his mind on the issue, Gallup concluded that “his new position is more of a net minus than a net plus for him.” Although 11 percent of independents and 2 percent of Republicans told pollsters they were more likely to vote for him, 23 percent of independents and 10 percent of Democrats said they were less likely. Last month, Democratic pollster Stanley Greenberg reached a similar conclusion. While 29 percent of respondents said they had warm feelings about gay marriage, 40 percent had cold feelings.

The same trend was found in the swing state of Florida. According to a Quinnipiac University poll in late May, 23 percent of independents and 7 percent of Democrats said they were less likely to vote for Obama because of his support for gay marriage; only 9 percent of independents and 1 percent of Republicans said they were more likely to vote for him. Voters without a college degree were slightly more likely to say they were alienated by Obama’s decision.

In another crucial swing state, -Virginia, analysts say that Obama’s support for gay marriage hurts his reelection bid. Forty-nine percent of voters said they disapprove of gay marriage while 42 percent said they approve of it, according to a June Quinnipiac poll. Steven J. Farnsworth, professor of political science at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, estimates that the president’s stance will cost him one or two percentage points in the Old Dominion this fall. “On balance, his position on gay marriage is a negative, but it’s not a big negative,” he says.

In other swing states, pollsters have not examined voters’ attitudes toward gay marriage in the depth that Quinnipiac did in Florida. Even so, most polls in these states have found the public cool to Obama’s position. In Ohio, 50 percent of voters reject gay marriage and 37 percent support it, according to a Public Policy Polling study in July. In Iowa, 45 percent of voters disapprove of gay marriage and 44 approve, according to a May PPP poll. In Wisconsin, 47 percent of voters reject gay marriage and 43 percent back it, according to a PPP survey in July.

Perceptive analysts concede these numbers likely overstate the level of public support for gay marriage because of voters’ tendency to tell pollsters the most socially acceptable answer on the phone and do the opposite at the ballot box. “You can’t say for sure. Certainly in Maine, it looked like [an effort to repeal the state’s gay marriage law] would go down to the wire, and gay marriage lost,” says Todd Eberly, a professor of political science at St. Mary’s College of Maryland.

In a couple of swing states—Colorado and New Hampshire—pollsters have found either majority support for gay marriage or opposition to repealing it. And Farnsworth believes that Virginia Republicans’ efforts to regulate abortion more strictly will cost Romney one or two percentage points in the state this fall.

Yet pollsters and analysts also say Obama must finesse his support for cultural liberalism. “If you’re not careful, you give the impression that you’re catering to special interests, and that’s a problem in Colorado. Colorado voters think of themselves as centrists,” says Floyd Ciruli, an independent pollster and analyst based in Denver, noting that Obama’s campaign is running an ad that accuses Romney of opposing abortion in the event of rape or incest.

Obama is running the same ad elsewhere, but unless he can seize on a Romney misstep on abortion or the Supreme Court decides suddenly to chuck Roe v. Wade, he is more likely to be hurt than helped by his pro-choice stance. Consider a Gallup survey from May 2008. In looking at voters’ attitudes toward abortion in the five presidential elections from 1984 to 2000, Gallup concluded that “the issue netted the Republican party’s candidate two to three points in [each] election.”

Of course, Republican presidential candidates have also run ahead of ordinary voters; as a supporter of Paul Ryan’s entitlement-busting budget blueprint, Romney runs this risk. Yet the Democrats’ nominees have been consistently more likely to do so. As Eberly concluded in a report for Third Way earlier this year, “one reason Democrats lose is likely because the folks who set the agenda for the party are more out of step with most of party voters than are the folks who set the agenda for the Republican party.” In fact, Eberly found that the ideological gap between Democratic activists and voters is more than twice that of their Republican counterparts since 1972.

Eberly expects the gap will continue this year. “It’s statistically significant. It’s real. These are very much the people you would think of as Reagan Democrats,” he says. “These Democratic nonactivists really find themselves perched between conservative Republicans and liberal Democrats. They can go either way.” And when Obama becomes the first presidential candidate to declare his support for gay marriage at one of the presidential debates this fall, he cannot expect these voters to go his way on November 6.

Mark Stricherz, Capitol Hill correspondent for the Colorado Observer, is the author of Why the Democrats Are Blue: Secular Liberalism and the Decline of the People’s Party (Encounter Books).