America as Less Than No. 1

By Daniel Henninger

WSJ.com

So this is a taste of what it will be like when

the American superpower starts shrinking. Enjoying

it yet?

After the humiliation of the United States losing

its AAA credit rating; after watching the American

stock market descend into chaos; after living for

two years in a $15 trillion economy unable to grow

beyond 2%, with unemployment rates rarely

experienced in the U.S., Americans have their first

whiff of inhabiting an empire in decline.

You could divide the country between those who

think that it wouldn't be the worst thing for the

U.S. to enter the long, falling autumn of its life,

as has Western Europe; and those who refuse to go

down, who'd do whatever they must to hold the

world's No. 1 ranking.

The U.S. is far from finished. The private

economy—from the biggest corporations to innumerable

dreamers launching start-ups—is fit and eager. But

make no mistake: The U.S. has taken a hard hit to

its 65-year status as the world's pre-eminent

nation.

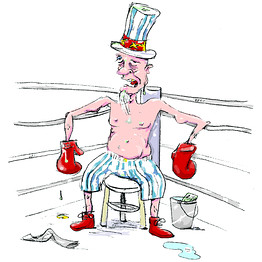

Uncle Sam at the moment is seated in his corner

of the global ring, gasping for breath, and no doubt

he'll come off the stool. But the cynical men in

other capitals—Beijing, Tehran, Moscow, Paris,

elsewhere—will be watching now to see just how much

fight the old boy has left in him.

The Standard and Poor's downgrade is nothing more

than bloodless analysts looking at the grim

mathematical reality of this country's long-term

social commitments and its ability to pay for them.

Something has to give, and what they see bending is

the long-term growth rate that since about 1876

raised the U.S. to its current pre-eminence. If

growth goes, your status goes. It's not complicated.

Ask Britain, once glorious but now burning.

In his magisterial study of world growth since

the year 1000, the late economist Angus Maddison

noted that the "golden age" for growth lasted from

1950 to 1973, with world per-capita GDP growing at

3%. Then in 1973 growth slowed in the U.S.'s

"follower" countries of Western Europe and Japan:

"Some slowdown in these countries was warranted, but

policy failings [my

emphasis] made it bigger than it need have been."

The gauntlet thrown down by the S&P downgrade is whether the U.S. will now commit "policy failings" that change it into a follower country. We'll get a first answer shortly from the 12 solons on Congress's debt-deal super committee.

It's good that S&P made so much of the political

stand-off in Washington. This implicitly recognizes

there is probably no middle way between the

Democratic and GOP answers to the social and

economic questions raised by the downgrade.

Going back at least to the Clinton presidency, Democratic policy analysts have promoted, as a middle way, various Western European "mixed-economy" models for the U.S.—generous national systems for health and welfare, with the economy kept going by tax-supported "investments" (spending) in infrastructure, education, research and the like. This of course is what Barack Obama has sought from day one.

The Democratic argument has been that the country

could maintain its remarkable economic success while

performing all these social goals, though with

cutbacks in defense spending. But there has never

been any sort of coherent

economic argument for how we could spend all

this money and maintain the U.S.'s long-term growth

trend. The S&P downgrade is at bottom a repudiation

of 50 years of Democratic economic theory, or its

absence.

What they've offered is essentially a dream,

often described by them as such. But if the dream

requires that Washington must somehow manage

spending on the scale now, then clearly the

middle-way dream isn't working.

The U.S. is not Germany or Denmark. Follower

nations can afford to do no more than maintain

contented populations. The U.S. bears inescapable

global responsibilities. President Obama's explicit

intention—Libya is Exhibit A— has been to back off

America's No. 1 footprint in the world to free

resources for the domestic dream.

What we're going to learn from this crisis is

that American exceptionalism means something more

than a vague claim to special status. More

substantively, it means the necessity to find

peculiarly American solutions to American problems.

A central attribute of our exceptionalism has

been flexibility. U.S. economic success is a story

of adaptive, efficient responses to history's

headwinds and speed-bumps—until now. A national

infrastructure bank would be the opposite of that

tradition. It'd be too big and too slow. The Obama

health-care plan, run through the 46-year-old

turbines of Medicare, is wholly at odds with the

needs now of a huge, complex country.

Washington is not America, and so optimism is

possible. Out in the country, some states are

showing with their public-pension reforms that

government flexibility in the face of economic

crisis is possible. A Washington able to recognize

the immediate needs of the downgraded superpower

would lift every identifiable burden from the states

and the private economy.

Here are two headlines from one day this dreadful week: "U.S. Productivity Falls" and "Truck Makers Face Fuel-Efficiency Rules." That is the path to being less than No. 1. It doesn't taste right.